Michele Neale sometimes brings Legos with her to do consulting work with clients. No, it’s not for killing time during break sessions. She uses them to make a point.

Sometimes during the training session, Neale will pass out Legos to attendees and instruct them to get to work building something. Piece by piece, they lock together Lego bricks, guided only by the ideas and images in their own minds.

And then she throws them for a loop.

“Halfway through I’ll stop them,” Neale says, “and I’ll say, ‘OK, we need this person to rotate one to the right, this person rotate one to the left.’ And you now have different teams working on different projects. And then I’ll say, ‘You have two minutes left to finish your project.’”

Wait, what? How can a team come into a project that is in progress and be expected to complete it adequately and on time? The obvious answer is, “They can’t.” Yet it happens all the time.

“It’s no different than how we might have to reassign people in production,” she says, referring to how employees are often asked to move to different areas of a manufacturing plant’s operations. “And as a leader, what did you do to tell them? Did you explain ‘why’ first? Did you have those conversations with them to share the bigger picture and the vision? Or did you just move people and get right down to it?”

The Lego trick is a prescient one. As a business growth consultant for Enterprise Minnesota, Neale understands well the psychology behind people’s response to change. She’s also, like most of us, acutely aware of just how much change is taking place right now. The coronavirus pandemic has upended life as we know it, forcing business leaders to grapple with a change agent like none they’ve ever seen before.

Luckily, Neale — who has presided over recent Enterprise Minnesota manufacturing workshops on the topic — has keen advice for anyone facing change in the coming weeks, months and beyond. There’s a right way to approach change and there’s a wrong way. With forethought and planning, manufacturing leaders can do it the right way.

Resistors and Curves

It’d be natural to assume that someone who has reached the upper echelons at a company has mastered the art and nuances of leadership, including how to guide a company through change. But, sadly, not all leaders have those skills. And bungling an opportunity to lead a workforce through major change can have catastrophic results. Like anything else in business, managing change is a skill leaders would do well to hone and sharpen.

The biggest obstacle to change, of course, is resistance. Neale says all resistors can be placed into one of three categories: I don’t get it; I don’t like it; or I don’t like you.

As the old axiom suggests, the first step in solving a problem is recognizing there is one. By that same logic, the first step in addressing the source of resistance is determining its type. When you know why someone is resisting change, you help them power through in constructive ways.

“I learned early on in my leadership career that, if I encountered someone who was my biggest resistor, I’d want him or her on my team,” she says. “I would want to make sure that when we came out with this new project, when we went to roll it out, that they were on board.”

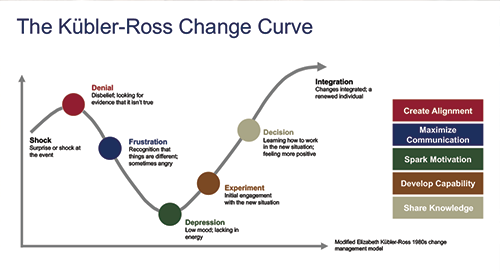

Neale says it’s also important for leaders to be cognizant of the Kübler-Ross change curve and how it applies to change leadership. The roughly V-shaped curve follows a familiar path: shock, denial, frustration, depression, experiment, decision and integration.

After the initial shock of an announcement of change (such as a new supervisor or a mask mandate), some employees may move quickly to denial, as in, “this can’t be true” or “this isn’t happening.” Leaders should make sure any change that happens is in alignment with company goals and mission.

Frustration sets in next. “This is ridiculous! Who came up with this idea, anyway?” an employee may say. Communication here is key. Employees deserve to know the “why” behind changes — big or small. Giving them as much information as possible can minimize frustration. Schedule regular meetings or check-ins, or perhaps institute a daily huddle routine to keep employees apprised of any developments.

“Listen, listen, listen,” Neale says. “And ask questions. Help create that open dialogue between you and your team.”

At the depression phase, employees may lack energy. It’s the leader’s job, Neale says, to address that by providing motivation. That motivation can lead to the next phase of the Kübler-Ross curve: experimentation. At this phase, the goal is for employees to realize, after trying something new, that the results were good. “Working from home wasn’t as bad as I thought.” Or, “Wearing a mask isn’t a big deal; it’s just a piece of cloth.”

The decision and integration phases come when employees begin to accept and buy into the change. They may feel more positive about their situation.

“In the past two weeks, I’ve had several conversations with clients about projects or initiatives they are trying to implement but aren’t experiencing success with,” Neale says. “It’s because they didn’t understand the change curve response, nor did they follow the change model. Whether it’s adding another shift, asking for overtime, implementing AS9100, ISO or ESO management systems, the dedication to change leadership is underestimated or ignored.”

Resilience

Neale’s presentation highlights another key area of change leadership: adaptability and resilience. To illustrate these values, she points to the story of a company called InLine Motion. Normally a manufacturer of equipment for the food industry, InLine sensed an opportunity when COVID hit and its business lagged. Its engineers quickly designed face shields and used social media to gauge interest. After a positive response, they manufactured thousands of face shields and backed it up with a bold marketing blitz. InLine soon found itself awash in orders for its new face shields.

Such a pivot wouldn’t have been possible without the company being both adaptable and resilient.

“When you build that culture of resiliency, then those who are resilient are going to be more likely to accept change, and maybe even embrace changes going forward because they see them as chances to grow and learn and experience new things,” Neale says. “It’s very similar to the continuous improvement environments. If you are a company that focuses on continuous improvement, your world is changing all the time. You’re constantly looking for those little things and asking, ‘How can I make my day better tomorrow? How can we have a better day today than we did yesterday?’”

Neale says she heard a recent example of a leader who could have used some resilience training. A manufacturer lamented feeling helpless in a situation where COVID-exposed employees may not be able to come to work.

“She was saying, ‘I’m worried about people who get exposed and then they have a two-week quarantine. What’s that going to do?’ Well, when you have those changes that come in, how can your team then bounce forward? How can they be prepared for those disruptions in the workforce and the workflow to be able to then know that we can do better?” Neale says. “Are your other people going to be able to come in and do more because they know that next week it might be them who’s out, and they don’t want to leave their teammates in a lurch?”

How a workplace responds to these kinds of pressures says a lot about company culture and its ability to be resilient. Neale says recent cases where some workers chose to stay home for COVID-related safety concerns can serve as a case study in how resilient your company is.

“There is a small percentage of people taking advantage of COVID so that they don’t have to work. But most people want to show up and help. Most people want to get things back to normal. Most people want to be a value to your organization,” Neale says. “When we talk about resilience, it’s also respect, fair treatment and appreciation. And it’s how that culture in your organization then comes together. We can have a we-can-do-this mentality as opposed to, ‘Oh my gosh! All these excuses. Are you kidding me? That’s going to shut us down!’ That tells me a lot about what your organization is going to look like.”

…

Featured story in the Winter 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.