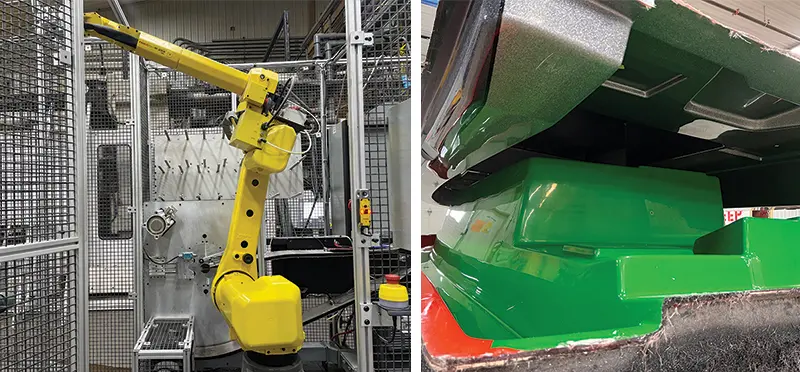

Jake Altendorf was immediately confronted by the competitive realities of the worker shortage when he closed the deal to take over Carstens Industries in December 2019. The Melrose-based fiberglass manufacturer makes car parts, ventilation equipment, carnival rides, and rock climbing walls for short- and medium-run clients looking to buy 1,000 parts or fewer per year. While the workforce had doubled over four years, its staff of 25 employees was struggling to balance projects from new clients while maintaining its current workload.

“It was like pouring more into a full bucket,” Altendorf says. Whenever the team attempted to take on new projects, something else spilled out. They couldn’t catch up. Altendorf tried all of the traditional things — job flyers, advertisements, and even temporary employment services, but the needle wouldn’t budge.

“We’ve always had hiring challenges,” he says, “and to start out my ownership in that time period was challenging and frustrating at the same time.”

In the midst of it all came an application from a candidate fluent in Spanish but speaking limited English.

Altendorf made the hire, excited for anyone willing to work. Then, the new hire referred a friend, the latter speaking no English. This was almost two years ago, but what followed and the lessons learned created a revolution in hiring practices for the company that continues today.

“It really took that one person to bridge the gap,” he says, “but one person who speaks English can keep five people working [who don’t].”

Since 2020, the company has grown from 25 to 50, and more than one-third of staff today speaks Spanish, with a handful of bilingual liaisons who help the company work across the language barrier.

The Carstens workspace displays signage in both English and Spanish, meeting notes are translated and dispersed, and bilingual team members help to answer questions from non-English speaking employees on policies, benefits, or disagreements. When larger training sessions are held, Carstens retains outside translators to communicate between supervisors and trainees.

Altendorf says the transition required interrupting production (during an already busy season) for long enough to handle training, which took even longer owing to a difference in language. However, once one department finished onboarding new staff, the increase in production would flood the next department down the line, mandating a company-wide cycle of growth. Meanwhile, a steady stream of referred applicants — many of whom were first-generation immigrants leaving behind professional careers — ensured finding candidates was no longer the hold up.

Altendorf cautions that his company’s growth doesn’t necessary reflect a “secret sauce,” and that new challenges rise up every day. What doesn’t waver is the company’s commitment to opening doors. He says it requires progressive policies at a business and municipal level, too, as the greatest obstacle for long-term employment is often basic necessities. Many of Carstens’ new hires arrive with no credit history, and, as such, no way to secure permanent housing.

The best solution requires a collaboration of business, politics, and people.

Decades of diversity

Altendorf and Carstens Industries’ willingness to hire across language barriers isn’t isolated — nor is their success in fending off workforce shortages. In Paynesville, Avon Plastics has a decades-long history of diversified hiring that has seen the company’s workforce grow from roughly 75 to 110 employees in the past decade.

It started in a trailer alongside Middle Spunk Lake in the 1960s. The company eventually relocated to a facility in Paynesville and manufactured medical devices, boat bumpers, and hula hoops. Founder Donald Reum holds a patent for the original plastic Slinky — a fortunate accident of plastic extrusion — along with 25 other patents.

Today, Avon Plastics’ vice president of inventory, logistics, and warehouse operations, Anne Haakenson, is the third generation in the company’s family leadership. Her father pivoted production to include composite decking in the early 2000s, and their brands include Armadillo Composite Decking, Master Mark Plastics lawn and garden products, Grid Axcents lattice panels, Quix Interlocking Tile, and TurboClip deck clips.

Haakenson says the Paynesville area has always had a diversity of culture and language, and the company’s hiring embraces that. Like Carstens Industries, signage at Avon Plastics is multilingual, and human relations manager Michael Ostvig speaks fluent Spanish. Ostvig says there’s a connection, an energy, that transcends language and culture.

“When you see someone working hard — no matter what the background — that speaks volumes,” he says.

Two years ago, the plastics manufacturer found a durable solution to its need for seasonal staff by employing a Spanish-speaking labor force that works between Minnesota in the warm months and southern states during colder seasons. Haakenson says the company now enters production every year with confidence in staffing, which is great for the company, but in return Avon Plastics has extended medical, dental, and financial benefits to seasonal employees — something that stands out when compared to other employers fighting for the same workforce.

If there’s one consistent takeaway from the experience of both companies, it’s that the first step is the hardest. Altendorf says he understands the hesitation business owners may feel when contemplating a multilingual workplace. Language is a basic building block in any team, and the difference of language can lead to misunderstandings and unexpected obstacles. Haakenson says that Avon Plastics, as an example, has needed to ensure that their benefits providers have staff fluent in Spanish to assist employees calling with questions regarding benefits and coverage.

Both companies agree the end result has been worth the work — especially having access to motivated, passionate employees who are often overlooked. Veteran employees benefit as well. For his own manufacturing floor, Altendorf says, “The early adopters, the people that embraced the language challenges at the beginning, have found that their workload is much more level because they’ve got support.”

And Carstens is now fully staffed and focusing on expanded training to cover illnesses, vacations, or shifting economic and marketplace circumstances.

Ostvig offers this advice to any company struggling to capture candidates and willing to look beyond traditional hiring barriers: “Be open to the possibility that people may surprise you — which they often do — and that it can be good and positive for everyone involved. It’s a simple approach, but I think it yields great results.”