Brian Frink and his wife Wilbur had their eyes on a Scamp trailer for 20 years.

Each year, they’d stop by the Scamp display at the Minnesota State Fair and dream of Northwoods camping trips, long drives across the U.S., making memories around campfires with a bottle of wine and each other’s company. Some day, they thought. Some day.

Some day came. Frink retired as a college art professor. He and Wilbur made plans, wrote a $500 down payment check for their Scamp camper and then waited. And waited. And waited.

They wrote that check in 2020. They picked up the trailer last January. But they knew they’d have to wait and didn’t mind.

“We thought it was worth the wait,” Frink says. “We knew it was going to be this way going in.”

You’ve definitely seen a Scamp.

As you’re gassing up your car on a summer Friday, you’ve no doubt gazed across the array of pumps to see a smiling gentleman gassing up his truck — behind which is hitched a curious, egg-shaped camper with a funny name printed on its fiberglass side.

The Backus, Minn.-based company that makes them can’t come close to keeping up with demand. If you were to order a Scamp trailer right now, you and your family wouldn’t be heading to the Northwoods with it anytime soon. Certainly not this summer. Probably not next summer, either. Like the Frinks, it’ll be more like a two-year wait.

But chances are, if you’re ordering a Scamp, you already know that. And you don’t mind. These nifty, affordable, campers have a cult following like few others. Scamp campers engender community, camaraderie, and loyalty. Owners and fans use websites, meet-up groups, and newsletters to discuss their Scamps and the adventures they get into with them.

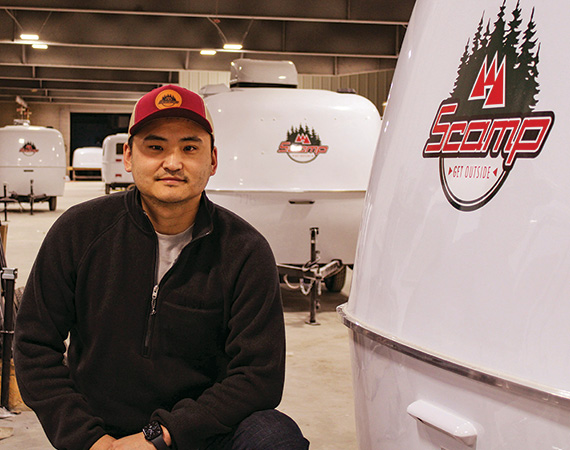

Scamp Trailers’ story is one of resilience. The company has not only been producing homegrown campers for 50 years but has also weathered a few “storms” — surviving a fire that put camper production on hold for nearly a year and navigating a pandemic, supply chain issues, inflation, and labor shortages. And in the last three years, the company has been under new management, as Micah Eveland, the son of former CEO and president Kent Eveland, took control of the company.

Micah Eveland wasn’t merely handed the reins of a successful company without knowing anything about it. He started out in customer service, answering questions over the phone. Then he became the warranty manager. Then he worked in purchasing. Then he became the plant manager. Eventually he took over when his father became ill. Kent Eveland, seeing the ship was in good hands, decided to retire.

While many companies are struggling to find workers and rustle up business, Scamp has the unique fortune of a young CEO with a personal stake in the company’s success, and a product with an uncommon demand.

Good problem to have

The backlog is a challenge. No company wants to tell its customers it’s going to take two years to complete their order. But Eveland says the backlog is the best indicator that they’re making a quality product that people want.

“It says a lot,” Eveland says. “It actually makes everybody here very proud to work here because it’s a sought-after product. Market studies show that we beat every competitor in every avenue of the business — price points, options, customer service.”

Eveland says one of Scamp’s biggest advantages is its lightweight fiberglass frame. A Scamp trailer, even the larger ones, can be easily hauled by a Honda CR-V or Toyota RAV4.

Scamp produces on average about 12 trailers each week. The company would like to grow that number and perhaps reduce the wait time to six months.

Jim Nagy, Scamp’s marketing coordinator, says the company is planning to add plant capacity to close the delivery wait-times. “Hopefully by this summer they’ll start pouring concrete,” he says.

One thing does concern Nagy. During the last two years, many people who felt isolated by the realities of the pandemic put in orders for Scamp trailers hoping it would solve their problems. He worries what will happen when some of them realize they actually don’t like camping.

This will cause the used trailer inventory to swell, which could impact future sales.

Young gun

This isn’t where Eveland thought he’d end up. He didn’t grow up with a dream of one day running a trailer manufacturing company. His dreams were taking him down a different path.

A gifted rodeo competitor in high school, Eveland was the state team roping and steer wrestling champion in 2006, 2007, and 2008. (He also continues to compete on the pro circuit.) Instead of running the family business, Eveland’s head was in the rodeo ring. He pursued training at the Minnesota School of Horseshoeing in Anoka.

But while he may not have wanted to pursue the family business, the family business pursued him. His dad called one day and told him someone had just quit in customer service, and he needed help.

“I said, ‘Oh, no,’” Eveland recalls.

But then he thought about what it might be like to work in the family business, and how he could make his mark on the already stellar brand.

He and his father discussed it, and Eveland pondered it some more. Then, when he went back to Backus in the fall to go deer hunting, he decided to take the job.

Eveland made his way from customer service to the warranty department, and then to purchasing, plant manager and sales. But even as he worked through the Scamp operation, he still assumed that this gig wasn’t permanent. He was helping his dad out, he told himself, until he finally figured out what he really wanted to do.

That changed five years after he started in his first role when his grandfather gifted him some company shares.

Owning shares instantly changed Eveland’s outlook on what he was doing at Scamp. It wasn’t just a job anymore. He wasn’t just showing up to put in his eight hours and head home. “Anytime you have some sort of ownership, it’s different. Just like your house. You’re probably going to take a little bit better care of it than somebody else’s house, right?”

Then, three years ago, his father fell ill while on vacation. And Eveland, who had spent several years learning every aspect of the company — and doing it now with a sense of ownership — stepped up. In his father’s absence, he assumed a level of responsibility he’d never had before. And he was successful. So successful, in fact, that his dad decided Scamp was in capable hands without him. Kent Eveland retired, and the Micah Eveland as CEO era began.

The fire

In January 2006, the unthinkable happened to the Scamp plant.

After most of the workers had left for the evening, fire broke out in the main production building. An office worker noticed flames and called 911, which prompted Backus, Walker, Hackensack, Pine River, Longville, Crosslake, Nisswa, Pequot Lakes and Ideal Township fire departments to respond. After trying for seven hours to douse the flames, the building was declared a total loss.

The fire destroyed all the fiberglass production molds, tools, equipment, inventory, and the main office that held most of the company’s records. Kent Eveland, the CEO at the time, said he’d hoped it wouldn’t take more than six months to be back up and running. But it wouldn’t be until the following December that Scamp resumed production.

“It’s one of the most horrible feelings in the world,” Eveland told the Brainerd Dispatch in the days following the blaze. “You watch fires sometimes, and sometimes they’re fun to watch, like bonfires. But when it’s your business, there’s nothing good about it. It’s just a bad deal.”

The company was insured, but the loss of production stung. Perhaps the only salve was this: The fire resulted in Scamp building a new 37,000-square-foot manufacturing and office facility on the same spot. Molds and equipment were upgraded, and in the end the facility and company were more modern and better suited to keep up with rising demand.

Production

The road from parts to ready-to-camp Scamp is a fairly typical assembly-line process.

The shell components are fabricated from fiberglass that comes to the factory in 50-gallon drums. The liquid resin is poured into molds that make up the distinctive egg-like shape of the Scamp camper. At the same time, the frame shop is busy manufacturing the chassis frame and assembling the axles and hitches. The fiberglass and frame components then meet at the beginning of the production line, and that’s where the assembly process starts.

The line has 12 workstations, including areas such as subfloor and electronics installation. Once the shell makes its way through all 12, it’s time for things like cabinetry and appliances. Finally, it’s time for quality assurance testing. And the person in charge of that is, shall we say, not the most popular worker on the line.

“That’s kind of an inside joke,” Eveland says. “I think they cringe when they see her walking toward them. Because they know something’s wrong.”

Most of the trailers that come off the line have something that isn’t “perfect.” Might be a scratch on the door that the buffer missed. Might be a slight imperfection in the stitch of a cushion. Whatever it is, the quality assurance expert finds it. If it’s a big enough deal to send back to the line for repairs, that’s what is done. If it’s invisible to anyone except the person who gets paid to notice this kind of stuff, it might be documented just so the company has historical data on recurring tiny flaws; a change in the process could be implemented down the line if necessary to eliminate even the slightest defects.

Supplies, inflation

Like most manufacturers, Scamp is dealing with the dreaded supply chain issues. But it’s not quite as urgent as it might be for others. Scamp’s purchasing team has ensured the company has enough supplies on hand to keep making trailers at its current pace. Eveland says that, if they approach low inventory, they scramble and hunt for parts to make sure the customers’ wait time isn’t extended.

“We build long standing relationships with our vendors. We can have those conversations (about supply chain issues),” Eveland says. “Scamp Trailers is nothing without our staff, we’re nothing without our vendors. So, if we don’t have good relationships with everybody, it’s not going to work.”

Nagy adds that the production line hasn’t had a down day throughout the pandemic, a testament to the loyalty of the company’s employees.

On the workforce front, Scamp is in a unique position. In a town of 322 people, it’s one of the major employers in town. Eveland retains employees through incentives and a culture of rewarding excellence.

“We strive to be the premier employer in this area, offering the best health benefits package and the highest pay for that line of work,” he says. “We’re very team oriented, and we try to stay relaxed as far as corporate rules go. We are still a small family business, but we try to be somewhat relaxed.”

And, small towns being small towns, word of decent wages and great benefits travels fast.

“I want every employee here to make as much money as they possibly can,” he says.

Scamp starts general laborers at $15 per hour. Once they are on the job, Scamp moves quickly to help employees find their best fit in the company’s production process.

“We try and see what you’re capable of,” Eveland says, “and quickly move that person to around $20 an hour.”

As for inflation, Scamp hasn’t been immune to the ebbs and flows of the national economy. With inflation at rates not seen since the 1980s, and with the Consumer Price Index up over 8% through March, it’s nearly impossible to be immune.

The refrigerators installed in Scamp trailers have increased in cost by 8%. The cost of fiberglass, the single most important component of the Scamp product, has increased by nearly 20%. One 55-gallon drum of fiberglass can complete, on average, one Scamp trailer.

Customer culture

Scamp trailers have a loyal following. There are Facebook groups where people share stories, websites that track meetups, and newsletters for people who want the latest updates about Scamp availability or trailer upgrades.

The clientele runs the gamut, Nagy says.

“A lot of them I would say are ex-hippies, people who like to travel around,” Nagy adds. “But then on the other side of the customer base are people who just appreciate something that’s built here. And these trailers have always been built here, going back 50 years. It’s kind of nice to know that you can still buy something that’s built, and has always been built, here in America.”

Frink falls somewhere in between. He certainly wouldn’t mind being referred to as a hippie. And he loves the idea of buying a trailer built in America. That notion, actually, is sort of in his blood. Growing up in Wisconsin, he watched his grandfather run his own trailer company, Tow-Low. He says the Scamp trailers, and the way they’re built in the Backus facility, remind him a lot of his grandfather’s work.

He and Wilbur already have a half-dozen trips planned for this summer.

“It’s a cool little trailer. And there is a lot of loyalty around these things,” Frink says. “We just have really enjoyed it. It’s a well-built trailer, and we’re happy we bought it.”

…

Featured story in the Summer 2022 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.