The Great Recession of 2009 blindsided Donnelly Custom Manufacturing the same way it whacked virtually every American manufacturer. By September 2009, sales for the Alexandria-based plastic fabricator had dropped 31% from the record-setting high it experienced a year earlier. Company President Ron Kirscht recalls that some customer accounts fell 20%, others by 40%.

“Everybody was down,” he says. Of the 21 sectors in manufacturing, 18 were down.

“All I know,” he continues, “is I wasn’t in the three that were up.”

Even at the softening distance of a 12-year recovery, manufacturers don’t forget how they were initially staggered by America’s sudden plunge into what seemed to be an economic abyss.

But once manufacturers recognized what caused the collapse — Wall Street speculators inflating then popping a housing bubble that derailed America’s interconnected economy like train cars lurching off a cliff — strategic planners such as Kirscht rolled up their sleeves and used the downtime to step back from an overheated marketplace and tweak their long-term plans.

Strategic planners in 2009 worked from an abundance of clarity about their business environment, says Steve Haarstad, a veteran strategic planning expert at Enterprise Minnesota.

“We knew what was happening,” he says. “We weren’t overconfident, but we knew what factors were at work and how they were interacting. We could make predictions and traditional business adjustments.”

Manufacturers assumed the giant pendulum of the American business cycle would eventually, if gradually, swing back toward prosperity. Enterprise Minnesota’s then-new State of Manufacturing survey revealed this shared confidence, as two themes repeatedly emerged in its polling and focus groups: “We’ve been through this before,” and “A recession is a terrible thing to waste.”

Says Kirscht: “We knew the fundamentals were sound.”

Hoping to jump on their competition as the economy improved, management teams studied improvements that would enhance their product array, their marketing and their in-house efficiencies. They ordered sales teams back on the road to reconnect with customers and prospects to discern market trends that might reveal possibilities for growth. Using that intel, planners considered acquisitions and new partnerships, tweaked product lines and pondered new ones, refurbished and serviced old equipment, bought new equipment, advanced their operations to the next levels of lean and found greater production efficiencies by training employees into new skill sets.

But that was then. And this is not then, at least not for everybody.

Today’s manufacturers navigating the current recession understand the circumstances differ from 2009 in two clear ways.

First, the big stick of the 2009 downturn hit all manufacturers equally. The damage from the COVID-19 economy is more selective. Manufacturers in supply chains that serve pharmaceuticals or the food industry, for example, are doing OK, if not thriving. Those serving, say, agriculture or the automobile industry, not so much.

The second factor is stealthier: It is uncertainty. Vulnerable manufacturers can’t assume the easy assumptions about the predictable strength of the post-2009 economy aren’t in play in 2020. Not even close. For them, the only real certainty in this surreal marketplace is that they don’t know what’s going to happen next. Their confidence in the Great Pendulum’s power has been overwhelmed (at least temporarily) by persistent COVID-19-related questions and uncertainties that evolve from politics and culture, not the logic of the marketplace.

“Someone has their hand on the pendulum,” Kirscht says.

Would the government allow them to stay open? Would they be listed as a critical industry supporting essential industries? How could they endure the bureaucracy of complying with new protocols and guidelines and rules in terms of hygiene, health, safety, protective equipment — all while social distancing? Answers to these questions could change at any time.

And there’s more: How well will public health officials predict and track the spread of COVID-19 infections? Will the virus mutate into something else? Will it just dry up and die? Will masks prevent the spread? Is temperature monitoring effective? Are social distancing tactics practical on the manufacturing floor? Will American pharmaceutical companies develop, manufacture and distribute a vaccine? When? Will it work? Will school opening decisions affect employee attendance?

Manufacturers find no solace from experts. They watch with a cocked eyebrow as cable-TV economists use their time on pundit panels to trot out visual depictions of America’s economic recovery. A V-shape? A swoosh? A reverse square root? It’s all entertaining, but manufacturers understand that these poor analysts don’t know any more than they do, because to do so would require knowing the unknowable.

The Haarstad model

Even within this muddle of ambiguity, strategist Haarstad fervently believes leadership teams should dive into planning, using the same tools they used a dozen years ago. “It is probably more important than ever,” he says.

But with a significant twist.

Haarstad says the shrewdest long-term strategy for vulnerable manufacturers in the COVID-19 economy may encompass just 90 days. If long-term planners in 2009 created strategic plans to give their companies a competitive advantage in the recovery, he says, COVID-19-era planning should focus on mitigating near-term marketplace fluctuations. “It’s about viability and sustainability,” he says.

“We don’t know what life is going to look like in six months. We have to abandon that long-term view and latch on to any glimmers of hope and convert them into opportunities for the business.”

-Steve Haarstad

Most manufacturers started 2020 with a positive view of their prospects for the year. When the State of Manufacturing pollster asked executives to rate their prospects for 2020, even as late as March, 89% were highly optimistic about their prospects for the year. But then things changed.

“Somewhere around March, COVID-19 hit,” Haarstad says, “and it changed their business, either for the better or worse.”

How well a manufacturer survives the upcoming peculiarities of the COVID marketplace, he says, may depend on developing a 90-day plan that creates some clarity amid the shadows of the current business environment. At its core, the Haarstad process urges manufacturers to reframe their vision of year-end success, and then design a path to that endgame using innovative brainstorming and a fanatical focus on a stripped-down set of data and priorities.

The reframed success, he says, could be broadly defined as growth, finding new customers, making investments or capturing a new market. Or it could merely be to stop the bleeding. Planners should represent this vision in a single initiative; the steps toward it should be guided by a carefully drawn short list of key decision indicators.

Haarstad describes his “sustainability” pandemic planning process as a showcase for “the power of narrowing.” It builds on answers to the same four existential questions that manufacturers would have answered, say, six months ago, when they plotted a more traditional three- to five-year plan.

- Who are we and why do we exist? What is our purpose? What’s our culture?

- Where are we now?

- Where do we want to be in the future? What’s our vision for the future direction of the company?

- How will we get there? What do we have to do to make the vision a reality?

“The answers may not be simple,” Haarstad says, “but the questions are.” His traditional planning assigns equal weight to each answer as a backdrop of a long-term strategic plan.

The particular strength of COVID-19 planning lies in what Haarstad characterizes as “the power of narrowing.” He compares it to driving a car. Drivers who navigate city streets at neighborhood speed limits, he says, can safely handle distractions like changing a radio station, talking to a passenger or glancing at a billboard. But driving safely at freeway speeds requires a higher level of focus. “It’s the same with navigating a company through a COVID economy,” he says. “We have to narrow our focus. We’ll stay in our lane, doing what we’re good at doing, without distractions.”

Data

Company data provides essential information in Haarstad’s COVID-era strategic planning.

“Data tells a story,” he says. “It helps us clear up uncertainty and evaluate options so we can make decisions for our business.” But current uncertainties, he adds, “require business leaders to make decisions about our business, not just monitor the performance of our business.”

More data, however, is not necessarily better. While modern manufacturers have information dashboards that can provide an overwhelming amount of data, Haarstad suggests winnowing to a handful when making decisions, relying equally on essential performance indicators (KPIs) and key decision indicators (KDIs).

“It’s OK to manage, manage the performance, but ultimately we need to make decisions to move the business forward and get better.”

KPIs and KDIs are essentially the same, he adds. “We are renaming KPIs as KDIs to emphasize the idea that we need to use data to make decisions for and about our business, not just monitor the performance of our business.”

KPIs and KDIs are made up of both leading indicators and lagging indicators. Leading indicators are activities that lead to results (such as customer contacts, quotes sent, the number of new customers, prospects added to the pipeline, and economic indicators like raw material pricing or home construction rates). Lagging indicators are results of the leading indicator activities (such as revenue, margin, backlog, customer profitability, warranty, etc.).

Haarstad says the following factors deserve attention.

1. Analyze top customers. Evaluate how they might finish 2020 and how their performance might influence your own. “Are they growing? Are they struggling? Do you need to change something with your relationship? If they are struggling, look for ways to support them,” Haarstad says. “If they are really hurting, you might look for ways to replace them.” On top of this, Haarstad urges manufacturers to analyze the profitability of customer relationships.

2. Keep tabs on your competitors. Planners should assess the condition of the companies with whom they compete for business, which starts, Haarstad says, with knowing who they are. His notion is that competitors may find their own competitive edge, at the planner’s expense. “You want to know if they’re growing, and you want to know if they’re pulling back,” Haarstad says. “Are they entering new markets? Have they tweaked their messaging? Depending on what you find out, you might need to take action to defend your position.” Those changes might encompass marketing or more aggressive price. On the other hand, Haarstad says, struggling competitors might provide an invitation to enter a new market or capture new customers.

3. Conduct a scenario-based SWOT analysis. Assess the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats based on how well your company has coped with the COVID economy’s constraints over, say, the past 12 weeks. “You’ll get different answers than if you just did a SWOT more broadly,” Haarstad says. “And based on your findings, take action: Leverage your strengths and fix your weaknesses. Shore up against the threats you identify.”

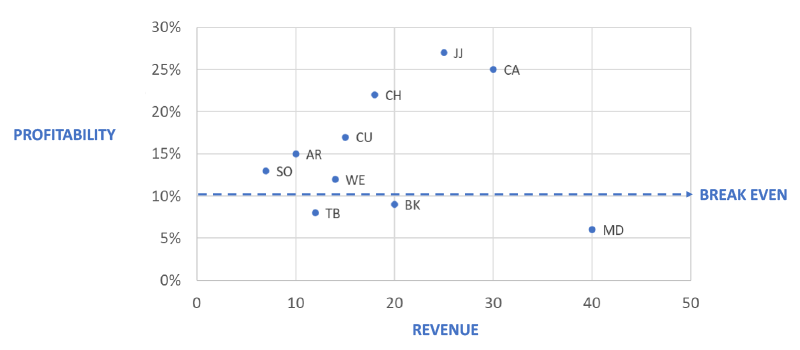

Analyzing customer profitability represents a key data point in Haarstad’s COVID-19-era planning model. He points to a client that produced a graph that plotted total revenue by a customer on the X scale and profitability on the Y. The company discovered, to its amazement, that its biggest customer fell below the break-even line.

The discovery forced the client to take action to move the customer above the line. They might have raised their price or improved their cost position. In this case, the company concluded the customer was not the best fit and referred them to a competitor.

Prospective hindsight

Reframing the endgame enables manufacturers to examine their competitive outlook from other angles. Identifying worst-case or best-case scenarios of a given situation can be powerful, according to Haarstad.

He advises clients to reframe their short-term strategic outlook by using a what-if planning tool called prospective hindsight. By using it, strategic planners conceive of hypothetical future events, and plot actions that will either minimize the potential damage (a “pre-mortem”) or enhance the possible opportunity (a “pre-parade”). “We often look at a scenario or situation from just one perspective. Reframing allows us to look at it from another angle. We can identify the worst-case scenario and our best-case scenario. And this can be really powerful because now we’ve put boundaries around it.”

Haarstad says prospective hindsight shares similarities with open brainstorming, but by limiting the conversation to a defined event, the insights and solutions will be more concrete.

“Hindsight is always 20/20; we can use this tool to change perspective and reframe the situation a little more broadly,” he says.

Here’s an example: Let’s say you have recruited an exceptionally prized employee. She came to the company with a rare combination of talent and experience. She’s a motivated employee with a diligent work ethic and gets along well with coworkers. Lucky, right?

But what would happen in six months if she unexpectedly walks into the boss’ office and submits her two weeks’ notice? The management team can use a prospective hindsight brainstorming session to consider the causes and consequences of that possible eventuality and ponder steps to avoid it or at least to minimize the damage. The net effect of the one-off possibility will likely have improved your overall attention to sharpen the company’s overall sensitivity to HR issues in general.

Planners will ponder her departure. Why might she quit? Did she get a better job? Was it closer to home? Did she get more money? Better benefits? Did her husband get transferred? Or did she simply want to change careers? If there are a couple of dozen reasons for her departure, Haarstad says, probably half would be beyond your control. But others — circumstances a company can control — deserve forethought.

Did she dislike the good ol’ boys culture on the shop floor? Did she have problems with an uncooperative coworker or manager? Did she think job expectations were poorly communicated? Were her responsibilities evolving into areas she didn’t want to pursue? Did she feel overworked, underappreciated? Did she fail to see a pathway to a promotion or expanded responsibilities?

A wise company would use the circumstances of this real-world pre-mortem possibility to sharpen its sensitivities on a wide variety of HR issues.

“These are ways to discover problems inside your building,” Haarstad says. “If you know about them, you can act on them and hopefully prevent that negative event from happening. That’s the value of the pre-mortem.”

Planners can use prospective hindsight in other ways to reframe their company’s outlook, Haarstad says. Consider this: Let’s say you operate a small contract manufacturer that provides machine parts and fabricated assemblies to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). Last year the company earned $5 million in the second quarter. During the second quarter this year, however, you lost two major COVID-sensitive customers, which immediately sliced 25% from your profits.

Haarstad says company managers might mitigate that loss by imagining a “pre-parade” year-end event in which the company has found ways to recover the entirety of that loss. As they look back from their hypothetical future state, what might they have done to squeeze more revenue onto their income statement? Did they capture additional income from existing customers? Did they diversify their product lines or create new products to offer to new and existing companies? Did they identify cost-saving efficiencies in new or better processes? Did they reduce non-value-added expenses?

In the final analysis, Haarstad urges all manufacturers to hew to their strategic discipline, whether they are currently thriving or struggling

…

Featured story in the Fall 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.