It was the mid-’90s, and Lowell, Inc., a manufacturer based in Brooklyn Park, had earned a solid reputation providing parts for computer hard drive manufacturers. But it lost a major client in an uncertain market and, as a result, Lowell watched its workforce shrink from 120 to 45 employees in six months.

Rick Cullen, today the company’s president, was shop supervisor at the time. He remembers layoffs every Friday.

“I still look at it as the darkest days of my career at Lowell,” he recalls. “Five million dollars of business one year, gone the next.”

Ron Spah, Lowell’s vice president of operations, says the loss of business forced the company to lay off some talented, valuable people.

“More than the riff-raff was let go at that point.”

“We’ve been forced to grow,” Spah continues. “We were forced to be better at programming, tool selection, processing and bringing up our expertise.”

Transformation

Lowell was founded in 1964 by partners Dave Lilja and Lowell Thorud (the company’s namesake), but Lilja quickly bought out the business. Dave’s son, Pat Lilja, is the current owner. He describes the company’s 55-year survival as the result of its ability to learn and adapt to changing business environments.

“Quality and service is what we survive upon,” he says. “Our existence is based upon change. Either you’re the best at it or you don’t make it.”

all its efforts to contract manufacturing of

medical device components, employing 85

people in its 51,000-square-foot facility.

When Cullen joined the company in 1984, the focus was on computer componentry, but when that business dried up, Lowell moved into serving the aerospace and defense industries, scoring major players such as General Electric, General Dynamics and Lockheed Martin and working on notable projects such as the Patriot missile system and smart bullets, capable of striking enemy combatants hidden around corners and behind cover.

In 1995, the company pivoted again when defense contracts proved difficult to maintain as work shifted overseas. Lowell created its first stainless steel bone screw. Medical devices and high-precision parts for implantable tech have been its bread and butter ever since.

“We’ve transformed,” Cullen says.

Since early 2018, Lowell has devoted all its efforts to contract manufacturing of medical device components, employing 85 people in its 51,000-square-foot facility.

Despite the evolving business landscape, Lowell is a company of innovators who embrace automation.

Automation

“With our automation format, you can do so much more per machine, and the machines are a smaller footprint,” Cullen explains during a tour of the Lowell facility. Where eight machines toiled before, now one carries the same load.

“We’ve been able to increase business and create more space,” Cullen says.

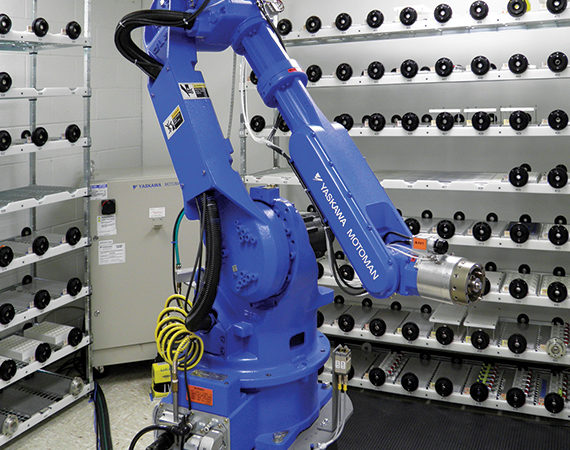

Space efficiency has been useful, but automated processes have also enabled Lowell to combat a shortage of machinists and engineers. Across the factory’s manufacturing and quality control branches, robots have taken over tedious manual labor. In the quality control lab, technician Brad has worked beside his robot for over five years. After so much time together, he says the autonomous arm is just part of the scenery, but the work it does eliminates a repetitive job, reduces user error and makes life easier for the company’s machinists.

And the facility is almost entirely paperless.

“There’s a PDF report that gets generated, and machinists can see it right there at their machine,” Cullen says. At their machine or anywhere in the world, in fact. The robotic arm tends to a team of three coordinate-measuring machines (CMMs), capable of tolerances equal to 1/800 of a human hair. The devices ensure each of Lowell’s components—used in heart pumps and spinal braces—are up to their necessarily high standards.

“At one time machining was about 80 percent of our cost, now it’s probably 40 percent. One machine can generate over $300,000 a year in revenue on weekends,” Stertz says.

It’s work that Cullen says would be impossible for human hands.

But transitioning to automated machines capable of swapping their own tools, adjusting processes on the fly, and performing quality control during production was a costly investment; the results took time to develop. It was the vision and trust of management that gave the go-ahead, but at Lowell there’s one man in particular credited with the robot revolution.

Revolution

Jim Stertz, Lowell’s vice president of automation and technology, points to a cluster of cutting machines surrounding a robotic arm nearby.

“These two machines and this robot have replaced five machines and three people because they run 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Stertz explains. “This is what robots are good at: waiting. People are not good at waiting. When the machine is ready, the robot’s there.”

But the machines still need a human touch at times, so Stertz developed a homebrew solution to remote monitoring. Nest-brand security cameras are placed around the equipment and are remotely accessible from any part of the world with Wi-Fi, which Stertz tested from Japan last April. If a machine runs out of tolerance, technicians receive a push notification on their phones. The cameras allow internal and external views, and a smartphone app (off-the-shelf, like the cameras) gives machinists remote control of the device’s computer terminal.

“No one can buy this. You’ll have to make it yourself,” he says.

Lowell’s attention to detail has paid dividends.

Yet, the numbers paint a clear picture.

“At one time machining was about 80 percent of our cost, now it’s probably 40 percent. One machine can generate over $300,000 a year in revenue on weekends,” Stertz says.

The robots also cost a pittance to operate—about 60 cents per day by his calculations, Stertz says, making any argument for human labor in a monotonous role moot. “Why should I sit there and do this all day long when a robot can do it very well? I can do something more valuable—and probably get paid more.”

What’s Next?

Pat Lilja’s team has perpetuated its founder’s legacy by rolling with the punches—and surviving at least one knockout blow. Lilja envisions even greater reliance on automation ahead with machines making the parts, and people providing support. But people are the key ingredient.

“As an employee, you give up a lot of yourself to come to work,” Lilja observes. “I try to be as positive as possible about having a work experience that is better than your home life so people would rather be here than elsewhere, assuming you have to work.”

And as for change? Lilja doesn’t fear change; he embraces it.

“It’s exciting to have things change. It’s exciting to go from this level up to the next. It’s exciting to see people come up with things that you didn’t have yesterday.”

…

Featured story in the Spring 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.