Few businesses reach their 100th anniversary without an ability to adjust to the changing demands of their customers.

It’s no stretch to observe that Hanson Silo wouldn’t have survived if it limited its focus to silo work. Failed former competitors litter the marketplace because they didn’t adapt to evolving customer needs. Founded in 1916, the company endured years of ups and downs by continually adapting to meet changing demands and break into new markets. Although “silo” remains in the company’s name, its operations are distinctly different from those early silo-building days.

While Hanson Silo once erected more than 1,000 silos per year, it now provides only maintenance to existing structures. As the agriculture industry shifted away from silos, the company moved to manufacturing precast concrete bunker walls, livestock feed storage and handling equipment, and powder coating, among other products. As the industry evolved, so did the company.

New Strategic Plan

As the fourth-generation owners of the Lake Lillian-based company, brothers Matt and Mike Hanson estimate that as much as 80 percent of the company’s current operations didn’t exist a decade or two ago. They think planning a strategic path for continued diversification will help sustain the future of the business and continue their forefathers’ spirit of ingenuity.

It’s no stretch to observe that Hanson Silo wouldn’t have survived if it limited its focus to silo work

Although they began developing a new strategic plan in early 2020 with Enterprise Minnesota Business Growth Consultant Steve Haarstad, the COVID-19 pandemic constrained the first steps in that process.

The brothers first discussed their needs with other manufacturing executives at Enterprise Minnesota-sponsored peer council meetings. The meetings allow industry leaders to pick each other’s brains, talk about the challenges they face, and bounce ideas off the group. Matt, Mike, and their father, Gregg, met monthly in different groups before COVID-19.

With the pandemic causing so much uncertainty, Haarstad says Enterprise Minnesota began offering virtual peer councils weekly or every other week through Zoom. Hanson Silo and other companies turned to the peer councils to hear how groups were responding.

“The COVID-19 situation has somewhat stabilized, but during the first four weeks of the stay-at-home stuff, and the week or two leading up to that, every day there was a new challenge confronting companies,” Haarstad says. “That’s why we went weekly with the majority of the groups.”

Even though people who were resistant to change left the company long ago, workplace practices have become ingrained at Hanson Silo and still require modification.

“A 104-year-old business with a culture that’s old and deep-rooted can be hard to control and modify,” Matt Hanson says. “It’s like playing whack-a-mole on culture.”

Getting the new strategic plan in place was crucial before the company’s agricultural work picked up in the spring.

“Spring is normally their super busy time,” Haarstad says. “They were pushing to accelerate the schedule and get a lot of it done as quickly as we could at the beginning of the year.”

Over several work sessions, a company working group established one-year and three-year strategic visions for Hanson Silo. The process spelled out its core values, mission, purpose, and how it differentiates itself from competitors. Haarstad regularly works with companies on plans like these, helping them understand how to grow revenue and strengthen their leadership cultures.

A lot of the work focuses on ironing out the company’s processes and taking stock of what resources it has and what it might need. Enterprise Minnesota helped Hanson Silo develop a skills matrix, for example, where the company looks at what its 50 to 60 employees are proficient in and what skill gaps the company needs to fill.

Many companies in rural Minnesota struggle to find the number of highly skilled workers they need to operate. Some companies have even had to relocate headquarters to alleviate the problem. The Hansons acknowledge that recruiting can be a challenge but have no plans to move.

The company’s existing workforce is excellent, Matt Hanson says, and it helps that so many are cross-trained. Having workers with broad skills makes it easier to shift them to wherever they’re most needed.

Compared to the challenge of recruiting new workers, the weather is a far more unpredictable obstacle the company has had to overcome. In a business with so many agricultural clients, weather often dictates how well a given season goes.

And unfortunately, Mother Nature hasn’t been kind the last couple of years, which has made diversification even more important as a strategy to overcome the variables the company has no control over. When agriculture business wanes, the company’s other divisions can potentially make up for it.

“Hanson Silo tends to be seasonal because of its connection to the agriculture market,” Haarstad says. “One of the things the company is trying to do is flatten that out to fill in the gaps.”

The company’s investments in new equipment in 2019 showcase its latest example of diversification. The new technology ramped up Hanson Silo’s floor slat manufacturing for hog and cattle barns. The need for the slats stems from an Environmental Protection Agency push for farmers to get hogs and cattle under roofs to contain manure, Matt Hanson says.

“That’s been where we’ve seen a growth pattern, and we’re happy we put that machine in. Now, we’re running it on weekends trying to keep up.”

Hanson Silo boasts of being Minnesota’s first dry-cast slat producer. The process involves using a low water-to-cement ratio to produce a harder, denser slat.

Using a higher water ratio leads to more pores in the concrete, reducing slat strength. Another unique production technique keeps the four-inch thick, 10-feet long hog slats flatter. Hanson Silo uses rotoscreed to level the slat’s top rather than hand troweling.

Manufacturing slats has become an essential and expanding part of the business. Haarstad says Hanson Silo’s team deserves credit for its creative approach to problem-solving.

“They have been very creative on their own,” he says.

A History of Innovation and Adaptation

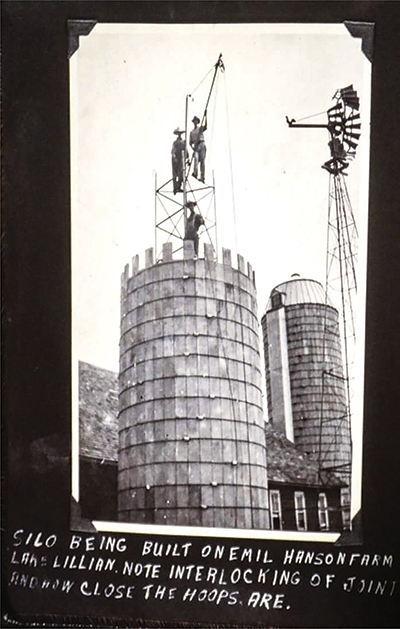

Hanson Silo’s spirit of adaptation dates back to the company’s founding. The business began in 1916 when founder Emil Hanson wanted to build a silo on his farm. He wasn’t satisfied with the poorly constructed silos he saw in the area, attributing the poor construction to the fact that local sand was too full of dirt and clay to produce durable concrete. He concocted the idea to use washed sand from the shores of nearby Big Kandiyohi Lake, which is now a common practice in concrete making.

His son, Newell Hanson, picked it up from there. The company’s first in a string of new designs and patents was an automatic silo stave machine in the 1920s, which sped up production. Next came a machine that made the first steel dome silo roofs in the 1930s.

The innovations continued into the 1940s. Newell and his son, Willard, patented the first self-propelled frozen silage chopper, a response to farmers demanding an easier way to unload feed from their silos.

By the 1950s, the business was growing along with its geographical reach. Manufacturing plants expanded into southern Minnesota and central Iowa.

More innovation in the 1960s expanded the company’s customer base outside the U.S. Farmers wanted a way to dig out silage during frozen and other tricky conditions, so Willard and Newell made a surface drive silo unloader for their customers.

One of the company’s more creative diversification strategies happened in the 1980s. While the agriculture industry was taking a beating, the company added a golf cart manufacturing plant called Shuttlecraft in Willmar. Hanson Silo got out of the golf game by 1991, but Matt Hanson says he still has one of the plant’s distinct looking carts.

Hanson Silo’s first precast concrete plant arrived shortly after in 1995. And more diversification came when Hanson Silo began powder coating a year later. The company also started manufacturing more products, ranging from truck beds to electronic scoreboards.

More recently, the company supplied 40,000-pound wall panels for a food manufacturing site. The building is one of many structures around the state featuring Hanson Silo’s concrete. The company’s current list of projects includes car dealerships, grocery stores, waste management transfer buildings, truck and diesel shops and storage facilities for state transportation departments.

Expanding the company’s powder coating capacity is another of its more recent diversifications. Powder coating is now a sizable percentage of the business, growing from a five-person team that manually painted to a computerized line.

The latest installation of new powder coating technology occurred right around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic—and the equipment arrived about a week after. Getting it up and running upgraded 25-year-old booths, Matt Hanson says, which will help the company powder coat more products, including utility trailers, industrial fabrications, icehouse frames, and tractor rims.

“You send us an order, and we send back powder-coated packaged parts,” Matt Hanson says. “We’ve been able to use that as a diversity strategy to hit markets that are still going.”

The Midwest remains a big market for Hanson Silo. The company’s precast concrete bunker walls, for instance, are popular in Nebraska and other corn-growing states.

“We go where the corn is,” Mike Hanson says.

Other aspects of the business have international reach. The company’s Easy Rake silage facer brought its products onto every continent but Antarctica. The Hansons name Canada, China, Australia, Uruguay and Russia among the countries where they have customers.

COVID-19 and Future Plans

The COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t made life easier for Hanson Silo’s team. Contract manufacturing work wasn’t humming like it usually would in spring 2020, but the Hanson brothers are confident the lull won’t last long.

“Just like most companies, we’ve experienced some change with COVID,” Matt Hanson says, adding that some contract manufacturing work has slowed down, “but we’re all sure it’ll come back sometime soon.”

After all the work to develop a long-term strategic plan before the agriculture season ramped up, COVID-19 also upended the company’s short-term plans. One-year and three-year plans can hardly factor in impossible-to-predict pandemics. But the team at Hanson Silo felt the planning work was important enough to push ahead and adjust the plans.

“Many of the goals and priorities had to be revised because the pandemic hit,” Haarstad says. “The short-term priorities changed.”

Mike and Matt Hanson grew up in the business, but both worked for Twin Cities-based companies as adults before returning to their family’s operation. Matt has been company president since 2007, while Mike is the director of business development.

They credited their father, Gregg, who remains active in the company, with having the foresight to diversify the business during his tenure. The company’s core business, silos, had been declining since Mike and Matt were children, so expanding into other areas laid the groundwork for the company to survive.

Keeping a family business going, the Hanson brothers acknowledge, comes with some pressure. They don’t dwell on it, but Matt Hanson says everyone knows most companies don’t make it to the third generation.

Even surviving long enough to pass onto a second generation is hard enough for businesses. Research from the Family Business Alliance found only about 30 percent of family-owned businesses make it to the second generation.

Survival chances drop precipitously from there. Only 12 percent of family-owned businesses last into a third generation, and three percent make it to the fourth or beyond, placing Hanson Silo in rare company.

Flimsy to nonexistent succession plans often lead to a family business’ demise. As the third-generation owner, Gregg Hanson eliminated that possibility when he took control of the company from his relatives, which led to Matt and Mike taking the helm.

More so than feeling pressure at maintaining a family business, the brothers express how having such a legacy inspires confidence. When Hanson Silo breaks into a new concrete market, it’s a good bet they’ve been making concrete longer than their competitors, and they’ve had more than a century to fine-tune the process.

“We’ve been making concrete for 104 years on the same farm,” Matt Hanson says.

Having more data at their fingertips than their predecessors also boosts confidence, making new ventures feel like less of a leap of faith than in the past. While success is still far from guaranteed, the Hanson brothers say being able to look at market research before diving in provides a higher level of assurance.

Over the next 10 years, they aspire to establish sustained growth. Mike Hanson says more acquisitions are expected, and the need for concrete in buildings likely won’t let up.

Setting 10 percent to 15 percent per year growth targets is a common goal among manufacturers. Haarstad says he knows Hanson Silo’s leadership wants to see steady growth in its existing markets. Matt Hanson says he’d like to see 20 percent organic growth, along with more expansions in the future.

Time will tell how those expansions look. If the company’s history is anything to go by, what Hanson Silo is doing now could be different from what it’ll be doing in a decade or two.

Having a Hanson at the helm going forward seems like a safe enough bet, though. During a recent fishing trip, Matt Hanson’s son, age 14, told him he wants to team up with Mike Hanson’s son, age 1, to run the company someday. No matter what Hanson Silo does in the future, Matt Hanson says, his ultimate hope is that a Hanson will be overseeing it.

“Passing it on to the next generation, the fifth generation, is the goal.”

…

Featured story in the Summer 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.