Some of us would like to think cybersecurity is someone else’s problem, that it’s the other guys who need to worry about it, that we’re too smart to fall for the email from the Nigerian prince who just needs a little help depositing $6 million into our bank account.

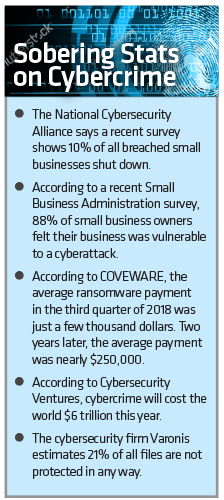

But the truth is, cybersecurity is a bigger threat today than ever. From major corporations with tens of thousands of employees to job shops with just a handful, cyber crooks are coming for your money and data in increasingly sophisticated and devious ways. How you address the threat to your business may determine if you even have one after the attack: Research shows one in 10 breached businesses doesn’t survive.

And for manufacturers hoping to be in the supply chain for companies with major Defense Department contracts, the rules for competing in that space are evolving just as rapidly as cyber criminals’ tactics; soon you’ll be required to prove you’re meeting stiff security standards.

Massive cybersecurity breaches with millions of dollars lost or millions of records compromised definitely get our attention. That happened recently when Solar Winds, a major information technology firm with tens of thousands of clients who use its software, was hacked by likely foreign cyber terrorists. The hack implanted malicious code into software updates and created a back door for bad actors to break their way into any client’s network using the software. It affected government agencies as well as major tech companies and touched the data of tens of millions of people. Experts say it will take years to repair the damage.

While this breach was unique in its cleverness, major companies have been getting hit by hackers for years. No surprise, right? Deep pocketed companies such as Capital One, Equifax and Yahoo! are prime targets for cash-motivated cyber terrorists.

But it’s not just large companies that are vulnerable to cyberattacks. Small- and medium-sized manufacturers have been hit hard too.

Focus groups in Enterprise Minnesota’s State of Manufacturing® survey revealed that a startling number of manufacturers have fallen prey to cyberattacks. In almost every focus group, someone told a story of getting hit with a ransomware attack, a common type of attack where hackers steal data and demand ransom for its safe return.

The threat is ominous. But by backing up crucial data and being smart about online habits, manufacturers can minimize the risk of getting hacked.

“The week we went into lockdown for the coronavirus we got hacked. It was ransomware. It cost about half a million bucks to get up on the other side of that. Thank goodness it didn’t cost us. I guess we had insurance for a big chunk of it. But it was an absolute nightmare.”

– A manufacturer, speaking in a focus group

Hassan Asghar, senior vice president and chief information security officer for Bremer Bank, which is headquartered in St. Paul, says every business’ security plan should begin with basic individual security hygiene.

“Phishing is the most common vector of attack,” says Asghar, referring to attacks that come into a business via emails with suspicious, clickable links.

Imagine this: An employee in a company’s accounting department gets an email that appears to be coming from the company’s CEO. The email tells the accounting employee that he needs money transferred to his account so he can make a work-related purchase. The accounting employee complies, sending money to the CEO using a link he provided.

Sound like something your employees would never fall for? Perhaps, but it works more often than you’d think.

“Ninety-one percent of breaches initiate this way,” Asghar says, who has worked with customers who have made this mistake. “The accounting person may not carefully look at the entire email and the domain, and they’ll just see the name and then process the payment. Then they find out the payment was actually processed to an account overseas that didn’t belong to this individual.”

Security hygiene also involves use of strong passwords that are difficult to guess, include some level of complexity and are lengthier, which could be in a form of paraphrase.

Manufacturers should also be vigilant about updating both antivirus and operating system software. Both are critical pieces in putting up a strong defense against cyberattacks. Antivirus software is constantly sweeping your system for malware. Operating system updates often plug holes that have been exploited by criminals.

Asghar also recommends making sure your connection to the Internet is secure. Some places are still offering free, passwordless Internet access, which Asghar says is all too easy for bad actors to exploit. The best fix for this issue is something called multi-factor authentication, and it’s a must for companies letting employees work remotely. Home offices may not be as secure as company networks, so logging into the network from home could open up a potential weak spot for criminals to break in.

Asghar recommends manufacturers use a virtual private network for remote work. VPNs use encryption to set up a secure, private connection that is difficult to hack.

Finally, Asghar recommends all businesses develop and practice incident response protocols. You don’t want to find yourself in the middle of a cyberattack and then realize you have no plan on how to respond. Get everyone involved — IT, marketing, operations, the leadership team. Every stakeholder should know their role in a cyberattack before the cyberattack.

“Then you can respond and recover,” he says. “By giving the key stakeholders a chance to practice those processes in case of an event, you’ll be much more crisp in terms of what you need to do.”

“Thanksgiving Day last year we were held ransom — all my PDFs and the engineering drive. We got a notification from our server that something was wrong, but by the time we caught it within an hour, it was too late. The ransom was in Bitcoin. And we actually negotiated with the people who were holding us hostage and got out of it for about half of the money they wanted. They gave us all our files back. But it’s real. We had mirrored servers, and we did all the stuff you’re supposed to do. But it just wasn’t good enough.”

Scott Singer, owner of cybersecurity consulting company CyberNINES, says he’s been working with a lot of companies on their cybersecurity issues lately. And not everyone is as secure as they think they are.

In some cases — where manufacturers are in the supply chain of major Defense Department contractors — national security can be at stake.

“Our country’s supply chain is built on small business,” Singer says. “A lot of the ways people are trying to attack a Lockheed Martin or a BAE Systems or a Medtronic is through that supply chain where it’s not protected. It’s about, ‘How do I find a way into that larger company because I really want to get into them?’ So, it’s critically important that we protect that supply chain and help that small and medium business be secure.”

The core of CyberNINES’ business is helping small- and medium-sized manufacturers comply with Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) around cybersecurity. Those regulations are in the midst of an evolution.

Several years ago, when the DFARS cybersecurity regulations were installed, the government allowed manufacturers to “self-attest” that they were meeting the cumbersome regulations.

But now with cybersecurity concerns at a fever pitch because of ransomware attacks and the Solar Winds breach, a system that once relied on self-attesting is about to get more teeth.

As of Nov. 30, any manufacturer in the supply chain of a government contractor has to go beyond the self-attesting and actually post a “score” through the online government website called the Supplier Performance Risk System portal. The scoring system is complicated, but it runs from a low of -203 to a high of 110; you lose or gain varying degrees of points for each line item on the standard. Manufacturers enter their score and the date they conducted their self-assessment. They also must enter a date by which they predict they’ll be in 100% compliance.

Disconcerting, Singer says, is the number of companies not taking the process seriously. He says he’s seen numerous cases where companies will make a rough estimate — rather than conduct a legitimate, conscientious audit of their security protocols — of what they think their score might be. These companies put themselves at risk if the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), which monitors contractor adherence to rules and standards, questions their score.

The DCMA might, in projects involving sensitive government data, audit potential contractors, Singer says. So, if a manufacturer posted a self-attested score of 60, and the DCMA audit reveals the real score to be closer to -140, Singer says the government is going to start asking tough questions.

“They’ll ask if you knowingly entered an incorrect score,” Singer says. “If there are any emails in your system that suggest you knew you weren’t in compliance but posted an incorrect score anyway, you’re subject to the False Claims Act. And that can take down your small business.”

The False Claims Act outlaws misrepresentations to the U.S. government and says you can be fined three times the amount of the contract plus $10,000 per incident.

“You can go to jail if you willfully do it,” Singer says. “It’s a little scary, and they’re starting to enforce it now.”

There’s a new system coming online that will replace the self-attesting scores. It’s called the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) system, and eventually it will affect all prime and subcontractors working with the Department of Defense (DoD). This system, which will roll out in phases between now and 2026, will require manufacturers to undergo third-party auditing similar to ISO certification.

The CMMC takes a different approach than the portal score system, however. It offers five “maturity” levels (level 1 is the lowest, level 5 is the highest) corresponding to a manufacturer’s cybersecurity preparedness. Which contract you can bid on depends on your maturity level.

By 2026, any company wishing to work with the DoD will need that certification.

“All of a sudden there’s huge teeth in this,” Singer says.

“About three or four years ago we had a case where it wasn’t ransomware, but it was wire fraud. We found out they were tracking emails between us and customers and banks. Since then, we’ve done a lot to make our servers more robust. We’ve done a lot more employee training. We know it was somebody overseas. And we lost a lot of money.”

Ransomware attacks have become among the most common forms of cyberattacks. Both the frequency and the financial damage they cause is growing fast. According to the University of Maryland, malicious hackers are now attacking computers and networks at a rate of one attack every 39 seconds. According to COVEWARE, the average ransomware payment in the third quarter of 2018 was just a few thousand dollars. Two years later, the average payment was nearly $250,000.

While all manufacturers are certainly advised to safeguard networks with anti-virus software, there are a few other methods of protection that could be just as helpful in the event of an attack: backing up your data and purchasing insurance.

When Enterprise Minnesota conducted its most recent round of focus groups, many participants who’d said they’d experienced a cyberattack had insurance. One even suggested that, without insurance, they may have lost their business.

Singer says that, while insurance is good, the best defense against a ransomware attack is a solid plan to back up your data. Like anything else, a system to do this automatically will vary in cost depending on the frequency of the backup. A system that backs up your data weekly or daily will cost far less than one that backs it up instantly.

Singer says backing up data frequently can position manufacturers to never having to pay the ransom at all.

“I don’t want people to be paying ransoms because it perpetuates the business model,” Singer says. “And if everybody keeps paying ransoms, then it’s not going to go away.”

By having a really good last-known backup, Singer says, it becomes a risk management process for businesses: How much risk can they accept, and how long can they go without having a current backup?

Still, the foundation of any cyber protection strategy needs to be on the so-called “end users”: employees. Almost all breaches start there.

Grant Burns, owner of the Bound Planet cybersecurity firm, says he’s seen many horror stories.

One case involved an email to an employee ostensibly from the company CEO asking her to purchase Best Buy gift cards for employee gifts. That CEO’s follow-up email asked for the serial numbers and security codes from the cards. Red flag.

In another case, shares Burns, an employee clicked on an email link that resulted in a ransomware attack. The company was shut down all summer because of it.

The solution to avoid this kind of calamity?

“It’s quick and easy to train your end user,” Burns says. “And you can start doing it right away.”

One tactic Burns uses with his clients is something called “ethical hacking,” where he sends emails to a company’s employees with suspicious links. He’ll do it to the same company multiple times and gauge progress. The goal is to teach employees to become shrewd emailers, the kind who are able to spot suspicious activity — such as an oddly spelled name of a coworker, a link with a strange spelling of a common name brand, or a bizarre request for money transfers — and eliminate it from the system.

“So, you’ll have employees saying, ‘I don’t want my manager to talk to me about clicking on this link so I’m going to scrutinize every email now,’” he says. “The expectation is going to be that we’re taking this seriously.”

While there still may be a good number of manufacturers who haven’t invested much in cybersecurity, Enterprise Minnesota Vice President of Consulting John Connelly says the future will look quite different. He predicts that just as ISO grew and became the norm for manufacturers looking to take their game to the next level and grow more profitably, so too will cybersecurity measures.

“And I expect it to go a lot faster, like maybe in four or five years,” Connelly says.

…

Featured story in the Spring 2021 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.